We do not trust the data we have not validated

Data Quality Checks with DQX

Introduction

This blog post is the second in a series focused on end-to-end data ingestion and transformation with Databricks, based on the principles of the Medallion architecture. The project will feature the vehicle datasets published by the Dutch RDW (national vehicle authority) and is aimed to exemplify a basic data processing workflow using core Databricks functionalities. In this blog, we will focus on data validation using DQX by Databricks Labs. The entire blog series consists of:

Blog 1: Data Ingestion Framework & Medallion Architecture - The secrets of bronze, silver, and gold

Blog 2: Data Quality Checks with DQX - DQX (YOU ARE HERE NOW!): We do not trust the data we have not validated

Blog 3: Dashboard Automation with Claude Code - Claude meets JSON: automating Databricks dashboards

Blog 4: Companion App for Data Exploration - You need a companion to explore your data

Blog 5: Asset Bundle Deployment - Deploy your project like a pro with Databricks Asset Bundles

Blog 6: Cost Optimization & Analysis - It’s all great, but how much does it cost?

Check out the project repo!

Data validation

Data validation is a critical step in any data pipeline by enforcing data quality standards. It avoids silent propagation of bad data. In the medallion architecture we clean and validate the data in the silver layer, ensuring that it does not pass to the gold layer and ends up in business aggregations, dashboards or machine learning models. There are many different tools available for data validation. This blog will dive deeper into our data validation approach that uses DQX.

About DQX

DQX by Databricks Labs is a data quality framework for Apache Spark that allows for defining, monitoring, and addressing data quality issues in Python-based data pipelines. Specifically, DQX is native to Databricks and Spark Dataframes.

Data checks form the basis of DQX. These are rules that validate on a row-, column- or dataset-level. The outcomes of the rule checks are dictated by the user and can be set as errors, which will filter out that data, or warnings, which will only add a warning column to these entries. Error data can either be left out entirely, or saved to a quarantine table, which allows for inspection of the data that does not comply with the defined checks.

Broadly speaking, there are three different methods for defining DQX checks.

The first approach uses definition files in JSON or YAML format. One advantage is their automatic version control when placed in your Git project. Their formats are as shown below:

yaml

- criticality: error

check:

function: is_not_null

arguments:

col_name: license_plate

- criticality: warn

check:

function: sql_expression

arguments:

expression: “LENGTH(license_plate) = 6”

msg: “License plate must be 6 characters”json

[

{

“criticality”: “error”,

“check”: {

“function”: “is_not_null”,

“arguments”: { “col_name”: “license_plate” }

}

},

{

“criticality”: “warn”,

“check”: {

“function”: “sql_expression”,

“arguments”: {

“expression”: “LENGTH(license_plate) = 6”,

“msg”: “License plate must be 6 characters”

}

}

}

]The second approach is using Python code for defining rules. Its main advantage is the potential for dynamic and programmatic rule definition.

python

from databricks.labs.dqx.row_checks import is_not_null, sql_expression

from databricks.labs.dqx.rule import DQColRule

checks = [

DQColRule(

criticality=”error”,

check_func=is_not_null,

col_name=”license_plate”

),

DQColRule(

criticality=”warn”,

check_func=sql_expression,

check_func_kwargs={

“expression”: “LENGTH(license_plate) = 6”,

“msg”: “License plate must be 6 characters”

}

)

]Lastly, it is also possible to store the rules in Delta Tables. This is especially useful if centralized management is required by the user(s). It does however add extra infrastructure to your project.

python

# Save checks to Delta table

dq_engine.save_checks(

checks,

config=TableChecksStorageConfig(

location=”catalog.schema.dqx_checks_table”,

mode=”overwrite”

)

)

# Load checks from Delta table

checks = dq_engine.load_checks(

config=TableChecksStorageConfig(

location=”catalog.schema.dqx_checks_table”

)

)Alternatives and why we opted for DQX

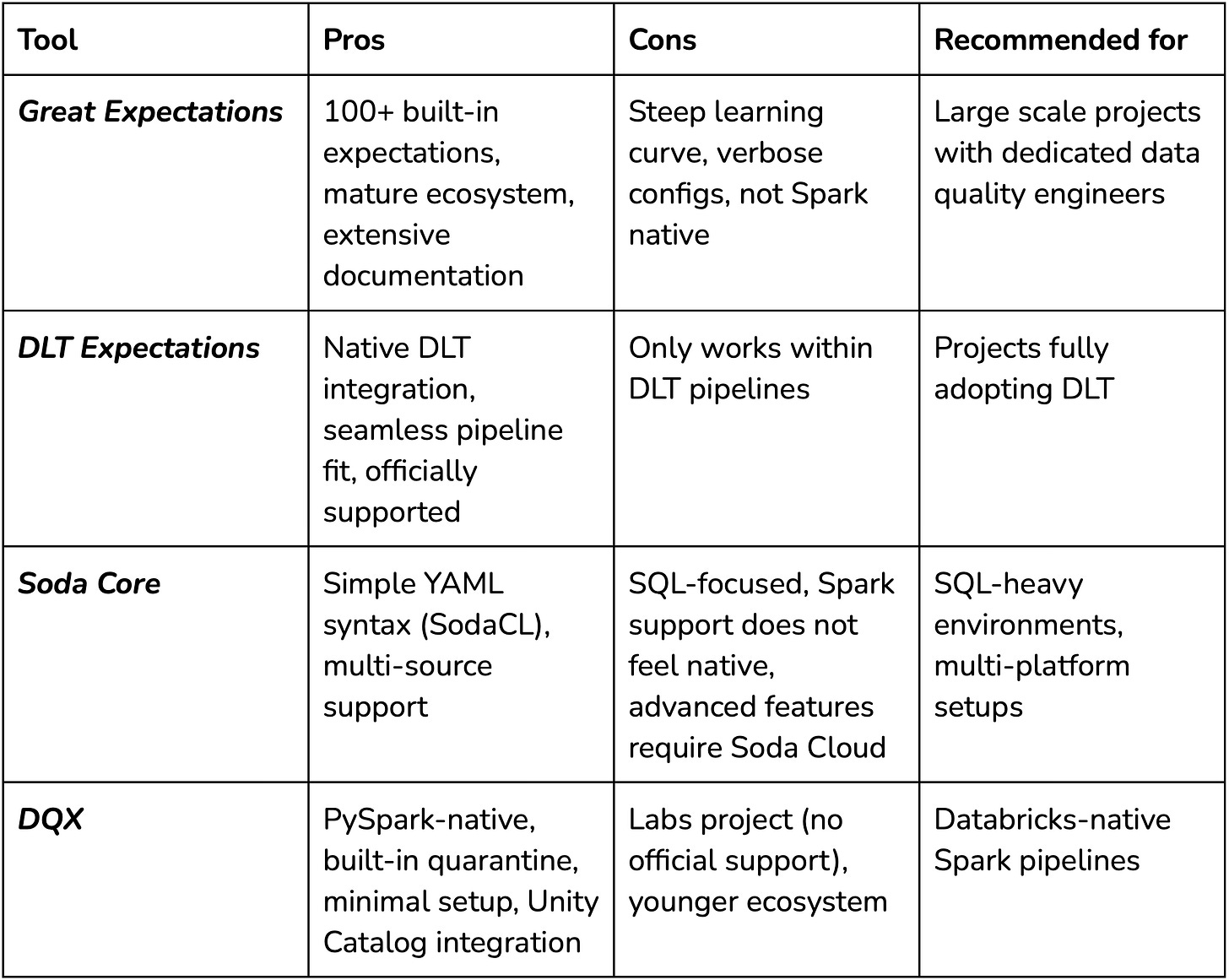

The data quality tooling landscape for Spark workloads has several options, each with different trade-offs. Some of the most popular alternatives include Great Expectations, DLT Expectations, and Soda Core.

Great Expectations is arguably the most mature open-source data quality framework. It offers 100+ built-in expectations, extensive integrations, and solid documentation. However, it has some overhead. There is a steep learning curve to using GE optimally, and its configurations can become very verbose. In addition, it was never designed for Spark in the first place, meaning it does not always leverage Spark’s parallelism optimally and can trigger unnecessary data movements or actions that harm performance. Depending on your purposes and resources, the complexity may outweigh the benefits, especially without dedicated data quality engineers.

DLT Expectations are built directly into Delta Live Tables and work seamlessly within DLT pipelines. It has become the obvious choice for users fully committed to DLT, however, we decided against using it since our use-case does not require the use of DLTs. In addition, DLT workloads run on more expensive compute than standard Spark jobs.

Soda Core takes a simpler approach with its YAML-based Soda Checks Language (SodaCL). It’s easier to get started with than Great Expectations and supports multiple data sources. The main downside to Soda Core is its SQL-focused core. And while Spark is supported through programmatic scans, it is not a native implementation. Advanced features also push you toward Soda Cloud, their commercial offering.

So why did we opt for DQX in our RDW pipeline?

PySpark/Databricks native: DQX operates directly on Spark DataFrames without translation layers or external dependencies. In addition it integrates cleanly with Unity Catalog and works on serverless compute.

Built-in quarantine pattern: the built-in methods support separation of valid and invalid rows out of the box. This is an essential component of the medallion architecture where bad data should not propagate downstream

Simplicity: Straight-forward setup for Databricks-focused projects. Defining checks in YAML is straightforward and requires only a few lines of code to apply them.

Flexibility: DQX checks follow SQL syntax and are easy to store. It even supports generating rules for other libraries such as DLT or custom setups.

Of course, DQX is not without limitations. Being a Databricks Labs project, it is not officially supported by Databricks (there are no SLA’s) - yet? The library is still relatively new, especially compared to its alternatives, meaning fewer available resources and less support. For our project where we demonstrate a pipeline with relatively simple validation requirements, these trade-offs are acceptable.

Workflow implementation

In our implementation, we decided to store the validation rules in src/rdw/dqx_checks. Each of the 10 tables has an individual YAML definition where its data validation rules are stored. There are several types of rules applied in our tables:

simple primary key

is_not_nullchecks to verify integrity. for the main table we decided to also check themake, thetrade_name, and thevehicle_typefor nulls.“is in” checks for categorical values, for example, `odometer_judgment_explanation_code

IN (’00’, ‘01’, ‘02’, ‘03’, ‘04’, ‘05’, ‘06’, ‘07’, ‘NG’). Can be applied when there is a limited range of applicable values for a column (and the values are known beforehand).Format checking: all license plates should be 6 characters long.

LENGTH(license_plate) = 6Date column integrity checking e.g.,

registration_date IS NULL OR registration_date >= ‘1890-01-01’

The DQX validation checking is carried out in the silver layer processing script; for more information on our medallion architecture implementation read blog 1 here. There exists a helper function apply_dqx_validation() which initializes the DQEngine object. The engine uses a databricks.sdk.WorkspaceClient as a parameter to initialize the Spark session. The WorkspaceClient automatically authenticates using your local Databricks configuration profile, or active Databricks instance when running on a cluster. Having initialized the DQEngine now allows us to load the stored checks using FileChecksStorageConfig and load_checks functions. In our case the paths are defined in the table configuration as table.dqx_checks_path.

It is then possible to validate the current DataFrame based on the configured checks:

python

# Initialize DQX engine

dq_engine = DQEngine(WorkspaceClient())

# Load checks from YAML file using FileChecksStorageConfig

checks_config = FileChecksStorageConfig(location=table.dqx_checks_path)

checks = dq_engine.load_checks(checks_config)

# Apply checks and split into valid and quarantined DataFrames

# load_checks returns metadata (dicts), so use

# apply_checks_by_metadata_and_split

valid_df, quarantined_df = dq_engine.apply_checks_by_metadata_and_split(df, checks)This returns both the validated- (cleaned) and quarantined DataFrames.

Quarantine

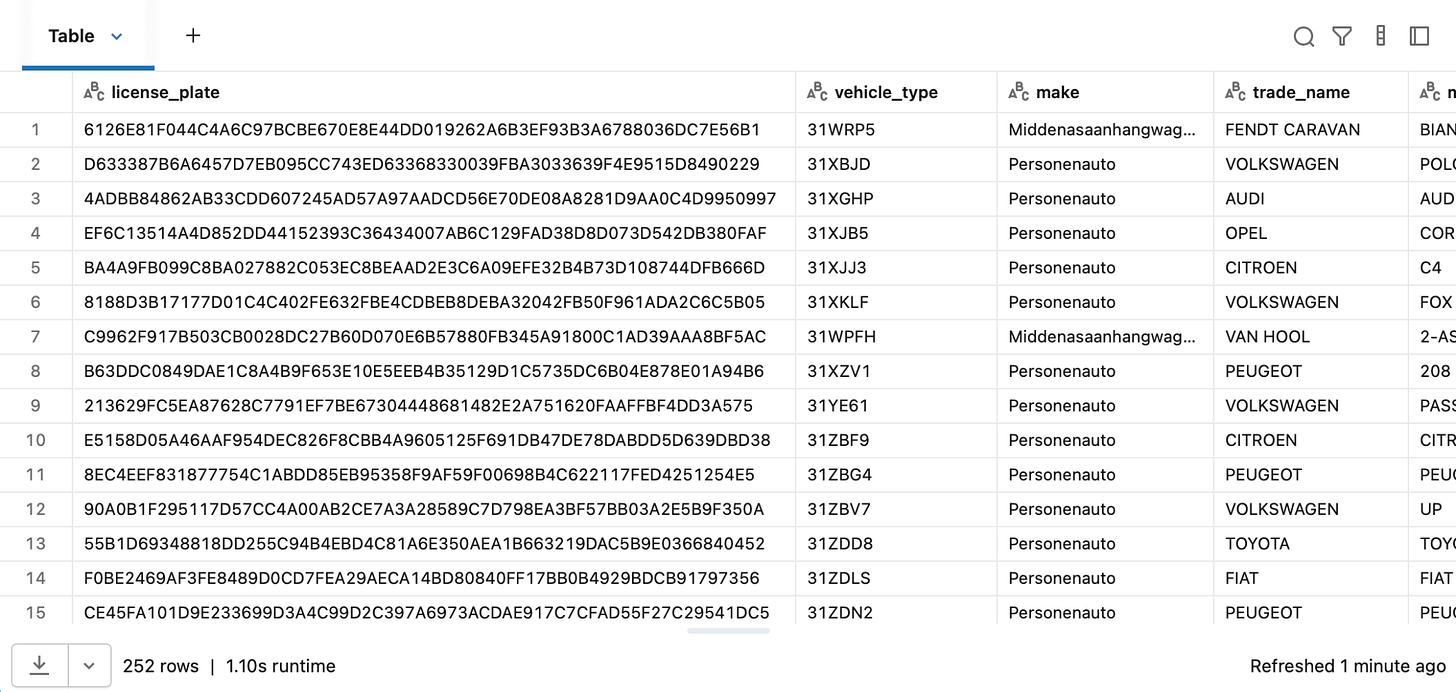

All data that does not comply with the validation checks ends up in the specified quarantine catalog. In our case we successfully caught a batch of data where improper formatting was found. Here, the license plate format check (LENGTH(license_plate) = 6) was triggered, and it seemed that all columns had shifted right. The `license_plate` column was substituted by what appears to be a row hash, hence all other columns had invalid, shifted data as well. The screenshot below shows the invalid data that was quarantined:

This provides a perfect example of how data validation is effective in real-world data, that is more often than not messy upon receival. It is good to note that in the most recent data, these issues have been resolved and the RDW most likely caught wind of this issue, so your quarantine results with the data may vary.

Conclusion

We found DQX to be a valuable addition to the project. Its implementation was intuitive and simple, using YAML-based rule definitions. The built-in quarantine pattern proved its value immediately, filtering out 252 malformed records from the ingested RDW tables, before the data moved further downstream.

For teams working in Databricks with standard Spark jobs, DQX offers a low-overhead path to data quality enforcement and validation.

In the upcoming blog posts we will dive deeper into various aspects of the project, such as a data exploration webapp, Databricks Asset Bundles (DABs), and cost analysis.